“Aciman may have gone out of Egypt but, as this evocative and imaginative book makes plain, he has never left it, nor it him.” — The Washington Post “With beguiling simplicity, Aciman recalls the life of Alexandria as his family knew it, and the seductiveness of that beautiful, polyglot city permeates his book.” — The New Yorker. Out Of Egypt 99,00 kn A mesmerizing portrait of a now vanished world. Aciman`s story of Alexandria is the story of his own family, a Jewish family with Italian and Turkish roots that tied its future to Egypt and made its home there for three generations, only to find itself peremptorily expelled by the Government in.

- Aciman is the author of the Whiting Award-winning memoir Out of Egypt (1995), an account of his childhood as a Jew growing up in post-colonial Egypt. His books and essays have been translated in.

- “Aciman may have gone out of Egypt but, as this evocative and imaginative book makes plain, he has never left it, nor it him.” ― The Washington Post “With beguiling simplicity, Aciman recalls the life of Alexandria as his family knew it, and the seductiveness of.

Release date: 01/01/1995

Genre: Nonfiction

“Most of my essays start with something personal. I try to find where the reader and me are going to connect; what geographical coordinates we have in common. This is also how I enter into dialogue with a movie or a book. I look for that something about me that has been manifested in an author’s work. Then I answer them in my work. And hope they will answer back again.”

Andre Aciman Out Of Egypt Mobi

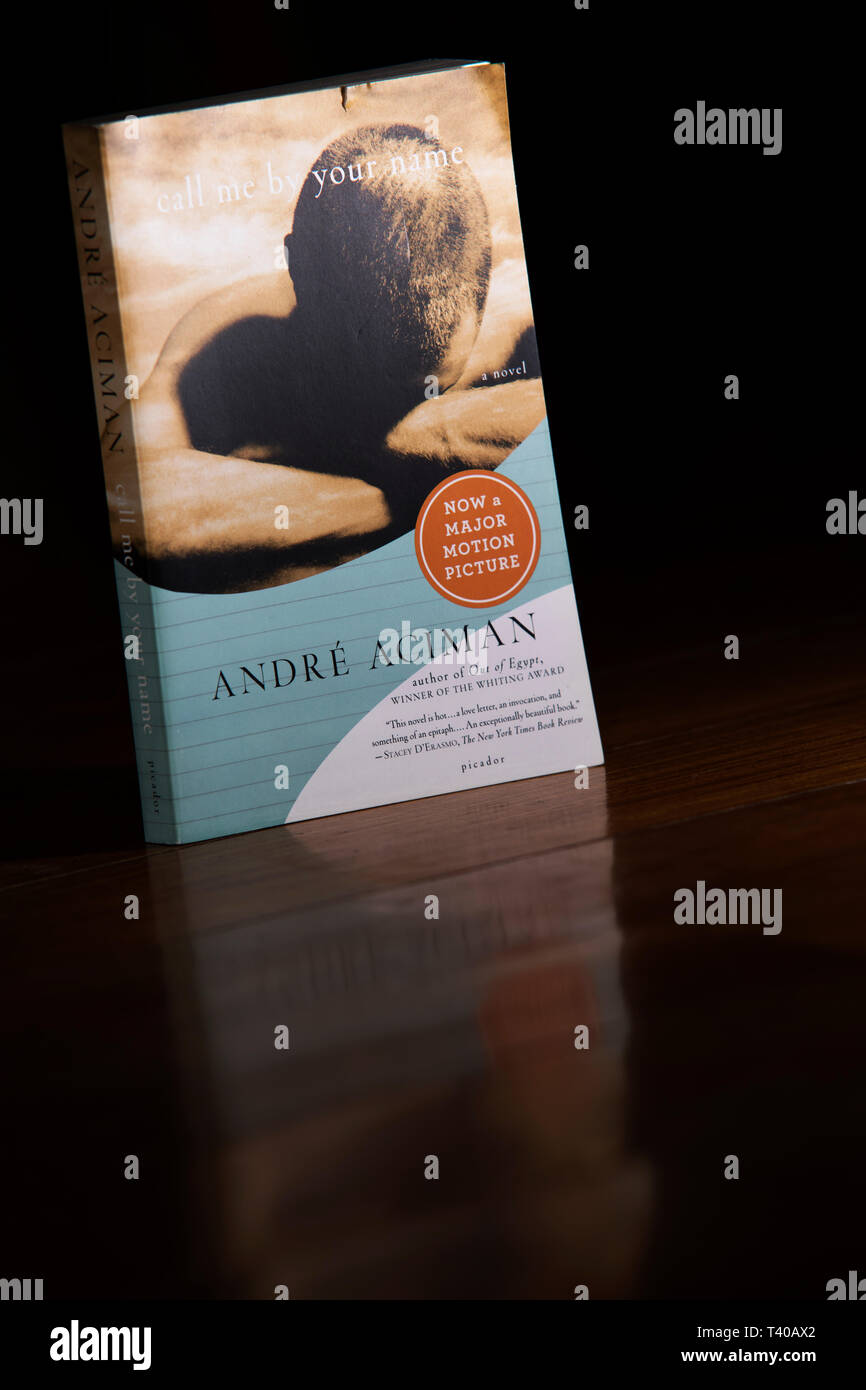

André Aciman, the author of Call Me by Your Name (CMBYN), is sitting in front of an overflowing bookshelf. His tone is soothing, his sentences are precise. He predicts the death of scholarship – “scholarship might be already defunct but could go on for a century or so”. Literary scholarship misses that “something essentially human” art works have. “Mediocre artists only talk to us about how to become a better human or become more civil. Those are noble prospects. But that is not what I am interested in.”

“I used books to stay in my room and close the shutters.”

When asked why he chose to study and teach literature, he says that nothing else interested him. “From the age of fourteen to twenty, all I did was read. And fall in love. But it never worked. I used books to stay in a room and close the shutters. Then I would not have to look outside at my part of Rome, which I hated. I was reading Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, The Brothers Karamazov. I would be in Russia really, just pretending to be in Italy.”

“Superficial, episodic things define our link with places. When I am in Rome, I am in the best place on earth. But I am not in love with Rome. I was put in a lovely hotel in London recently. I loved London because of that. How superficial is that?”

Out Of Egypt Andre Aciman Summary

André Aciman seems like the kind of person that likes to enjoy life – but never stops questioning it either. In the same way, the characters of CMBYN and Find Me are insiders, happy multicultural elites, still hurt by the passing of time and struggling with life’s ephemerous relationships.

“I get excited about parties. Not about my work.”

“The reason I wrote Find Me was that I was on a train. Next to me stood a beautiful woman, with a dog. She told me to hold the dog while she was going to the bathroom. Something was going on between us. Then, she left. So, I wrote about that.” Find Me tells the story of the love story between Elio’s father and Miranda, a young woman he meets on a train. It is filled with the poetic of lost opportunities, years lived without purpose, that find a resolution in love and the birth of a new child.

“I wish I could be excited when I start a new book. I am more excited when I have a new friendship. When I am invited to dinner with a group of friends – before COVID at least. I get excited about parties. Not about my work. I am a fundamentally insecure writer.”

When I tell André Aciman I would not have guessed that, he lists the manifestations of this insecurity in his writing. “If I were confident, I would write shorter sentences. I would be more factual, use ‘maybe’ less. Those are all ways of retracting what I am saying. In CMBYN, Elio goes to Oliver’s bedroom and sees a towel under the door. He knows why it is there, but he never says it. I never say it”. I imagine him in his New York University classroom, pointing out the signs of hesitant writing in the great novels of the past. It is impressive to see him levy his capacity of literary analysis against his own writing.

The movie made from CMBYN, starring Timothée Chalamet and seeped in the light of the Italian countryside, brought André Aciman to the mainstream. “It is a wonderful feeling to watch one’s words being transformed into a movie. I told the producers they were free to do what they wanted. The only thing I changed, was to strike down a scene where the parents were talking about Elio and Oliver’s relationship. I wanted the audience to know the father knew about them only in the scene where he discusses it with Elio, at the end of the movie. If not, it was anti-climactic.”

Oliver is an assistant to Elio’s father, a professor; the age difference means their relationship, and Elio’s sexual awakening, take place in the secrecy of the villa where Elio, his parents, and Oliver are spending the summer.

Out Of Egypt Andre Aciman Goodreads

“Aciman is widely credited for having written the defining love story of the modern era.”

Of the multilingual set of the movie, André Aciman says it “felt like being back in Egypt – where my mother tongue was French, but we spoke Greek, Italian, Arabic at home. So, I was very happy on set.” André Aciman was born to a Jewish family in Egypt, who eventually had to leave in 1965 because the Israeli-Arab wars were making it dangerous for his family to stay. “Now, I am always invited to Egypt. But I don’t feel secure enough to return”.

From his study, Aciman looks at me with a smile and says he is “going to speak to me about the rooftop in return” – the rooftop where I read his book, that I mentioned in my contact email. “That rooftop has something to do with me, since you wrote to me about it. So I am speaking to you about it in return”. This seems akin to his vision of art as a long conversation between humans, and artworks as mirrors of our own selves, “intrinsically human” productions that cannot be explained by scholarship. This will to “speak back” to people about their experiences, could also explain the sense of nostalgia-tainted comfort that one gets from reading CMBYN and Find Me.